In the beginning were… the principles.

Perhaps few times in life have we stopped to reflect on the true meaning of the word principle. That is, on the fact that there is not only a synonymy, but a real identity between principle, understood as a beginning, and principle in the meaning of doctrinal or philosophical foundation or of fundamental criterion for the enunciation of physical and chemical theories.

Leaving aside this second question, which is not marginal, and concentrating on the aspect of conceptual theory, we must surrender in the face of yet another non-trivial banality, that is, the evidence that the principles are at the beginning, that is, at the beginning, before events have taken form, before existence has passed from potentiality to actuality. Before the games have been played, in short.

Indeed, they should be the principles that inform and shape everything that is about to happen.

It seems like an obvious, minor step; instead, it is a crucial junction.

Everyone – or almost everyone – wants to have principles on which to model their existence: he is a man of sound principles and in principle I agree they are two expressions – among many – widely used to indicate the presence of pillars that support the ‘framework of action or thought.

But for the principles to be sound, and therefore to be able to bear the weight of everything that comes after, producing positive effects, they must be formulated before anything else.

First, fortunately, it does not indicate a strictly temporal sense: the principles can be formulated – or rather, can be developed – for the entire duration of our lives; they can even change, or even turn upside down. One of the characteristics of intelligence is its ability to rethink itself and get back into the game by even imperceptibly shifting the point of view and the consequent perspective.

In this case, first can be understood as in front: in front of the great mass of beliefs, judgments and prejudices, uses and habits and everything that belongs to our innermost world.

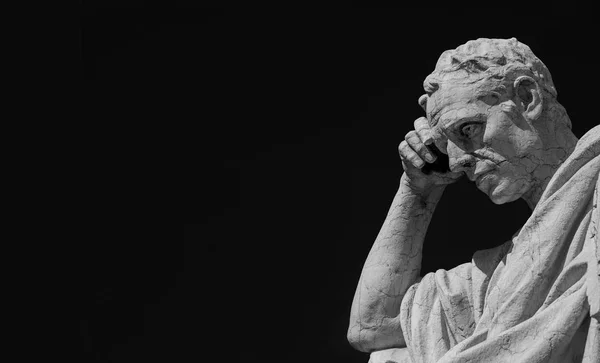

First, in front and also above: it is known that a good view – in this case, of human affairs – can be enjoyed from a raised point of view, from the top of a hill, even if it is not very high. The higher you go, perhaps on a plane or on a rocket to space, the more you realize exactly how things are; and we often feel amazed because at ground level we had no idea how the environment in which we lived was really structured.

Astronauts see things that normal humans will never see; and even more telescopes sailing in space. The details escape us, but the overall picture is understood much better.

The principle, therefore, cannot be something that is structured while immersed in a situation: that is by definition the domain of prejudices and traditions; of hearsay and it has always been done this way. In short, about the lack of autonomous criticism.

The principles according to which we structure our lives instead arise from a personal and autonomous critical vision, refined over time; and the more the criticism arises from a detached and global vision, the more the principles will be healthy and well structured, capable of directing existence in a precise direction and capable of giving well-being to those who follow them.

Put this way, it seems simple; indeed, simplistic. Good principles are formed thanks to the experiences I live day by day, and are automatically structured over the years thanks to a filtering process that eliminates the negative things and keeps the positive ones; these principles, consequently, are very good and can do nothing but lead me to a rosy and perfect existence. That’s how I lived happily ever after.

Let’s hope.

Things are obviously very different: second thoughts, stalemates, contradictions, a sense of impotence, declines in interest or simple tiredness play a far from negligible role along the path that leads to the formation of opinions. Possessing a principle – or a series of principles – is a long and delicate process, which has no predefined phases and is often the result of an itinerary that is not very straight or not at all straight, dotted with meetings and opportunities for reflection; and often also U-turns. It is not certain that the change of course is always a disastrous and negative event. We are the sum of all the people we have met, we usually hear, and it is very true: the example – more than a thousand words – has a decisive weight in illuminating the path we want to take during life.

One of the mantras of the Path of Blessing (The Earth is spherical and has no real boundaries) gives the measure of how it is necessary to proceed when formulating a principle: that is, it is necessary to take a step back to contemplate reality as a whole – or at least, that part that interests us – from a privileged, all-encompassing point of view. Panoramic, one might say.

This is precisely where the contemplative moment comes in: exactly like when we arrive at the top of a mountain and start admiring what opens up to our view, so the meditative moment opens up the scenery of our soul. It is tiring to climb a mountain; it is equally tiring to find the concentration – and once again, the silence: this time the internal one, the most difficult of all silences – to look at our deepest interior. In both cases, the more demanding the ascetic moment was, the more impressive the views that open up are.

Professional or sentimental choices, gender choices, abortion, euthanasia and divorce, presence of the divine in one’s life; or, strategies on how to deal with suffering or communication with others, are just some of the subjects on which we can focus our attention from time to time.

The broader and more important the topic, the more necessary it is to take steps back to have a broader view and to be able to draw useful conclusions. This type of spiritual activity must be done in solitude and silence, with calm and passion. Just like a sport, the meditative moment also requires assiduous, regular and constant exercise. Achieving true inner silence is a difficult practice, but not impossible: it is precisely the daily exercise that makes us able to understand if we are going in the right direction and if there is progress, even if minimal, or if we are immobile. We do not expect a spectacular and sudden illumination; we do not believe that we can arrive at pure asceticism in a single step and that we can clearly discern problems and solutions – by formulating, precisely, ironclad and all-encompassing principles – with ease. Patience and humility, once again, are the way to the solution.

Many spiritual and religious paths, using sometimes very similar techniques, teach us to look at things with detachment: stages such as silence, meditation, distancing from emotions and passions, pure contemplation follow one another.

Like all human realities, spiritual practices are also a daily journey, a continuous becoming, with steps forward and sometimes leaps backwards. This is precisely the difference between principle and prejudice, as we said before: both are before events and direct them, but the former is a continuous becoming and is subject to the filters of discernment and reflection; the second is a fixed reality, often derived from the thoughts of others and not subject to any criticism.

The road is not easy, but not impossible either. It brings surprising results: it is said that if every man practiced meditation for at least ten minutes a day, all conflicts would disappear in just one generation.

Something that we need more than ever today.

Commenti disabilitati - Comments are closed